Theater Kid

The fluorescent lights in the drama classroom hummed like they were trying to tell Jason something he couldn't quite understand. Outside, the southern Oregon rain hammered against the windows in sheets, turning the parking lot into a mirror that reflected nothing back but gray. It was October 1987, and Jason Hartley was sixteen years old, sitting in the back row of folding chairs, wondering what the hell he was doing there.

Through the rain-streaked glass, he could see the parking lot's charging stations—those boxy retrofitted units that looked like they'd been designed by someone who thought the future would be all right angles and chrome. A student's Honda was plugged in, its dashboard screen glowing pale green through the windshield. Everyone had screens now. In their cars, on their wrists, in their pockets. The world had gotten smaller and lonelier at the same time.

"You'll love it," Lenora had told him a few weeks earlier, leaning against his locker with that casual confidence only seniors seemed to possess. She had dyed-platinum hair and wore too much eyeliner. Jason had been half in love with her since she'd asked him for a cigarette behind the gym. She only liked girls though. "Drama's easy. Mr. Carlson is cool. Plus, you've got that thing."

"What thing?"

"I don't know. You're watchable. You've got a face."

Jason did have a face—a long, angular one that made him look perpetually worried, which wasn't far from the truth. At home, his mother was probably already in her Skren ComfortView headset even though it was only three o'clock, settled into her bedroom with an overflowing ashtray and a Margaret Atwood novel she'd never finish. The visor's soft blue glow would be seeping from the edges, casting shadows on her face as she disappeared into medical training simulations or soap opera feeds. His father was likely in his own room, door closed, sealed inside his Skren SonoScape headset listening to NPR archives with the volume turned low like he was afraid someone might hear him existing.

Things were better now than they used to be. Jason remembered the years before his mother got her nursing degree—the screaming matches, the food stamp frozen dinners, his father's arms crossed as he gave up fighting and retreated to his small bedroom. Now there was money for groceries without checking the bank balance first. Now his parents just avoided each other instead of destroying each other. Progress, Jason supposed, though the house still felt like a museum where everyone tiptoed around exhibits they were afraid to touch. Except now the exhibits wore headsets and nobody had to look at each other at all.

"Let's start with some warm-ups," Mr. Carlson said, clapping his hands once. He was young, early thirties, with a neat beard and wire-rimmed glasses. Everyone knew he lived with his "roommate" Derek in a house on the edge of town. Nobody said anything about it, but everyone knew. "Jason, we haven't put you on the spot yet. Come up here."

Jason's stomach dropped. Around him, the other students—mostly girls and a handful of guys who wore vintage clothes from the Goodwill—watched with the kind of neutral curiosity you'd give a new species at the zoo.

"I want you to walk across the stage like you're late for something important."

Jason stood and walked across the makeshift stage area, feeling his limbs move like broken puppets.

"Again. But this time, believe it. What are you late for?"

"I don't know. Class?"

"Make it matter. Make it life or death."

Jason tried again, and something shifted. He imagined he was late getting home, late before his mother finished her third beer and disappeared into her visor for the night, late before his father sealed himself in his audio tomb. His stride changed.

"There," Mr. Carlson said. "That's it. You felt that, right?"

Jason nodded, breathless, embarrassed by how much he had felt it.

The auditions for The Odd Couple were held on a Wednesday afternoon that smelled like floor wax and teenage desperation. Jason read for several parts, stumbling over Neil Simon's rapid-fire dialogue but finding something in Oscar Madison's slouching defeat that felt like home.

He got cast as Vinnie, one of the poker players—a nothing part, barely any lines. But it was something to him. Lenora hugged him when the cast list went up, and he could smell cigarettes and Aqua Net in her hair.

Rehearsals became the center of his universe. The drama room was warmer than home, fuller. People laughed at jokes Jason made without meaning to be funny. Mr. Carlson called him "a natural" once, and Jason held onto those words like a talisman.

The character Cecily was played by a junior named Beth who had braces and a laugh like synth chimes. During a break between scenes, she sat next to him in the back row and shared her Red Vines.

"You're good," she said.

"I have like three lines."

"Yeah, but you make them count. You're not just saying them. You know?"

He didn't know, but he nodded anyway.

After rehearsal one evening, Jason saw Mr. Carlson reviewing footage on a Skren MiyoVox Pro-48, one of those chunky shoulder-mounted camcorders that had flooded the market after the engineers at Skren figured out how to cram AI analysis into consumer electronics. The machine sat on the prop table, its boxy black body catching the stage lights, chrome accents gleaming. Mr. Carlson was watching the tiny flip-out screen, scrolling through blocky green text.

"What's it say?" Jason asked.

Mr. Carlson looked up, smiled. "Honestly? I don't pay much attention to the metrics. But it's good for reviewing blocking, seeing what the audience sees." He tilted the screen toward Jason. Numbers scrolled past: ENGAGEMENT METRIC 7.4/10.0. GESTURE AUTHENTICITY 82% OPTIMAL. "The machine thinks we did okay."

Jason stared at those numbers, transfixed. Someone at RadioShack was selling used MiyoVox units for two hundred bucks. Jason had been saving money from his job at the 7-Eleven, originally planning to buy a better car stereo. But the idea of seeing himself the way others saw him, of having a machine tell him exactly what worked and what didn't—it felt like the answer to a question he hadn't known how to ask.

He bought the MiyoVox the next Saturday. Carried it home in its foam-lined case like it was made of glass.

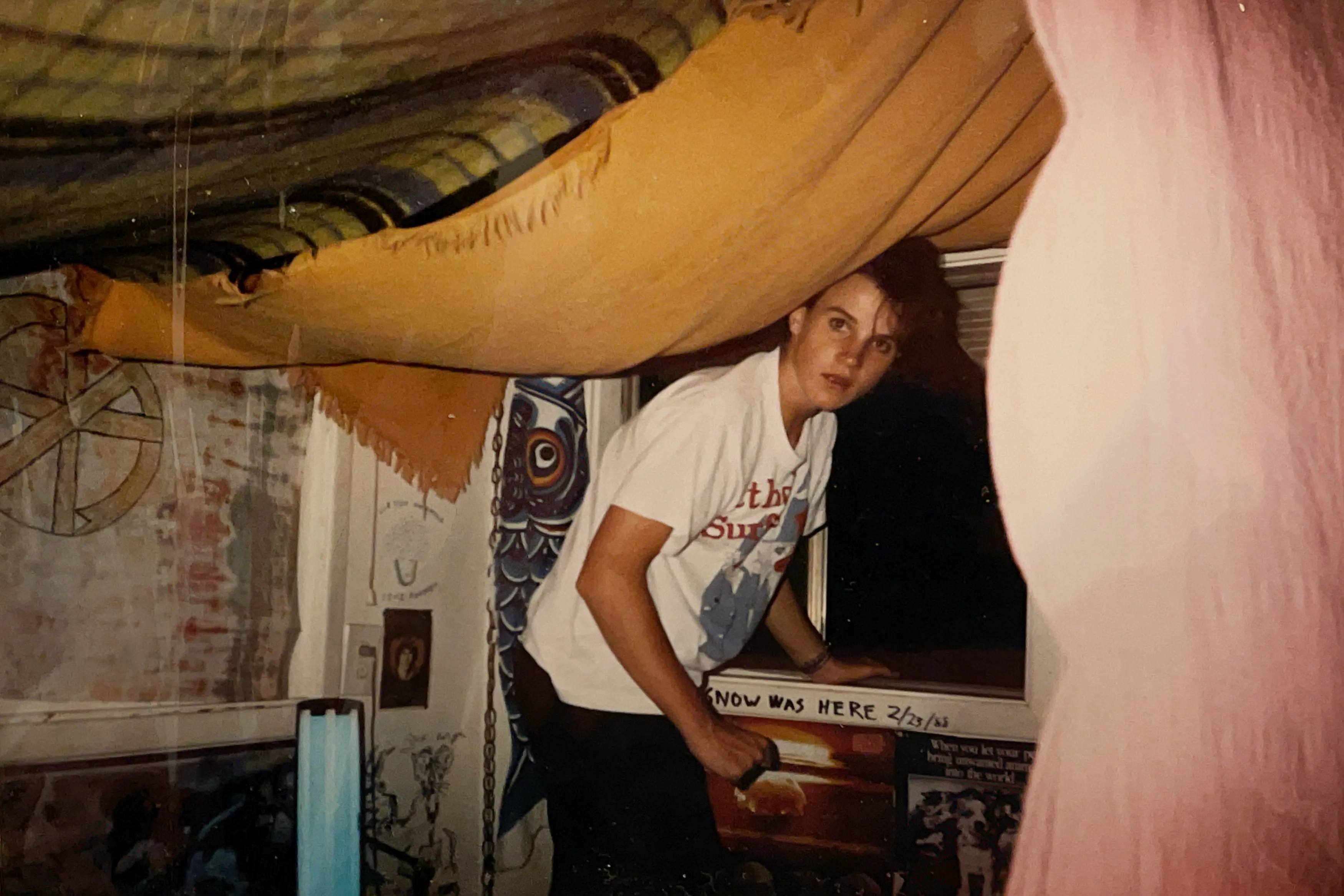

Jason's bedroom became a studio. He'd set up the MiyoVox on his desk, angled toward the space where his bed met the wall. After his parents retreated to their separate rooms—his mother's door clicking shut at 8:30, his father's at 9:00—Jason would pull out monologues from the plays Mr. Carlson had lent him and perform for the camera.

The MiyoVox would record for as long as the VHS-C cartridge had space, then Jason would rewind and watch himself on the tiny screen. After thirty seconds of mechanical whirring, the analysis would scroll across the display:

PERFORMANCE ANALYSIS COMPLETE.

The synthesized voice would emerge from the tinny speaker, each syllable pronounced with equal emphasis, no natural rhythm: "I am pleased to inform. Analysis is now complete."

ENGAGEMENT METRIC: 5.8/10.0 VOCAL PROJECTION: INSUFFICIENT EYE-LINE DEPTH: 41% OPTIMAL RANGE

"I regret to inform that vocal projection is insufficient quality. Eye-line depth demonstrates 41 percent of optimal range parameter. It is highly advised to increase volume parameter by twenty percent and maintain eye-line depth intensity. Thank you for your cooperation with MiyoVox system."

Jason would rewind, try again. Louder this time. Looking directly at the camera. He'd watch the numbers climb: 6.2. Then 6.9. Then 7.4.

Each increase felt like proof of something. He was getting better. The machine said so.

He spent hours this way, The Smiths and The Cure playing softly from his boombox while he performed and re-recorded, performed and re-recorded. After a while he stopped watching himself in the playbacks; he only saw the machine's analysis. His mother never knocked. His father never emerged. The house was three people in three rooms, all of them watching screens, all of them alone.

Beth kissed him behind the stage curtains a few weeks later, and Jason felt like he'd finally done something right. They hooked up twice more after that—once in her car, once in his. Both times were fumbling and brief, but they meant he was the kind of person things happened to.

But even as it was happening, part of Jason was calculating how he'd describe it later, wondering what engagement metric it would score.

The show ran for six nights. Jason's parents didn't come to any of them. His mother said she had a shift, which was probably true. His father said he didn't "really get that kind of thing," which was definitely true. Jason told himself he didn't care, and almost believed it.

A year went by.

David Brennan was a legend in their small town's theater scene—a director who'd supposedly almost made it in Los Angeles before crawling back to southern Oregon to torture high school students and community theater actors. He had a graying ponytail and wore scarves even in summer. When he announced auditions for Mother Hicks, half the drama class signed up just to say they'd worked with him.

Jason auditioned on a whim, expecting nothing. He got cast in the ensemble—a nameless member of the Depression-era chorus, few lines, mostly reactions and movement. It should have been disappointing, but David made it sound important.

"The chorus is the soul of this piece," he announced at the first rehearsal, pacing the stage like a caged animal. "You are the voice of poverty, of desperation, of America's forgotten. I need you to dig deep. I need you to bleed."

Jason brought the MiyoVox to the third rehearsal. During a break, he recorded himself running through the crowd movements, then watched the playback in the corner of the room. The green screen flickered with data.

GESTURE AUTHENTICITY: 73% OPTIMAL SPATIAL AWARENESS: ACCEPTABLE RANGE

"I am pleased to inform that gesture authenticity demonstrates improvement factor—"

"What the FUCK is that?"

Jason looked up. David was standing over him, face red, veins visible in his neck.

"It's just—I'm reviewing my blocking—"

"You're feeding yourself into a goddamn machine. You think you can engineer your way to truth?" David grabbed the MiyoVox, looked at the scrolling metrics with disgust. "This is what's killing theater. You people with your optimization and your parameters. GET OUT. Come back when you're ready to bleed for real, not for a fucking algorithm."

Jason's face burned. His hands shook. He packed up the MiyoVox and left, sat in his car in the parking lot for half an hour, unable to drive, unable to cry, just sitting there listening to Big Black combined with rain drumming on the roof.

But he came back the next day. He came back and worked harder. He left the MiyoVox in his car and stayed after rehearsal to practice his movements, to memorize everyone else's blocking so he'd never be in the wrong place. He watched David work with the leads and absorbed everything—the way he coaxed performances out of them, the way he made them strip away their defenses until something raw and real emerged.

But at night, alone in his room, Jason still pulled out the MiyoVox. Still recorded himself. Still watched the metrics climb: 7.8. Then 8.3. Then 8.9. He knew David would hate it, but the numbers felt like proof that he was improving. Proof that he mattered to something, even if it was just a machine.

One night after a particularly brutal rehearsal where David had screamed at him for five straight minutes about being too calculated, too mechanical, Jason came home and found his mother already sealed in her ComfortView, his father already locked in his SonoScape tomb. The house was silent except for the ambient hum of their immersion systems.

Jason set up the MiyoVox in the hallway. Pointed it at his mother's door first. Through the gap, he could see her lying on the bed, the bulky visor strapped to her face, foam padding molded around her eyes, the thick cable snaking down to the beige console box on the floor. The soft blue glow at the edges of the headset illuminated her cigarette smoke. She wasn't moving, wasn't responding to anything in the physical world.

Jason recorded for two minutes, then moved to his father's door. Same thing. His father sat upright in a chair, the SonoScape headphones covering his ears like a helicopter pilot's headset, eyes fixed on the primitive screen showing NPR audio waveforms and scrolling transcripts. He was nodding slightly, but to what? To nothing Jason could hear. To nothing in this room.

Back in his bedroom, Jason played the footage. The MiyoVox whirred through its analysis cycle. The green text scrolled:

PERFORMANCE ANALYSIS COMPLETE.

"I regret to inform. No subject engagement is detected."

SUBJECTS: NON-RESPONSIVE TO ENVIRONMENT UNABLE TO CALCULATE PERFORMANCE METRIC ANALYSIS ERROR ANALYSIS ERROR

Jason watched those words repeat. Even the machine couldn't comprehend people this absent. His parents weren't performing. They weren't even present. They were somewhere else entirely, and the MiyoVox's algorithms had no category for that kind of disappearance.

He put Ministry's "Thieves" on his boombox, turned it up until the grinding, mechanical rhythm rattled his desk. The industrial percussion matched something breaking in his chest. He rewatched the footage of his parents again and again, that grinding beat underneath, and felt like he was documenting the end of something.

At the next rehearsal, Jason stopped thinking about David's notes and the MiyoVox's metrics simultaneously. He just performed. Let himself feel the weight of Depression-era poverty, channeled his mother's absence and his father's silence into the nameless character's movements.

After dress rehearsal, David watched the final scene in silence. When the house lights came up, he nodded once.

"Better," he said to the cast. Then, looking directly at Jason: "You're almost there."

That night, Jason recorded the same performance in his room, running through the movements and reactions. The MiyoVox analyzed it:

ENGAGEMENT METRIC: 6.4/10.0

Jason stared at the number. At rehearsal, he'd felt more present than ever before. David had acknowledged it. But the machine said he'd gotten worse.

For the first time, Jason wondered if the numbers meant anything at all.

Megan Summers had perfect hair—that's what Jason thought every time he saw her. Raven dark with just a hint of blood-red and feathered like she'd stepped out of a Tiger Beat magazine. She was a junior, one year younger than him, popular without being mean about it, and so far out of Jason's orbit that he'd never even considered talking to her.

She came to opening night of Mother Hicks. Jason spotted her in the third row during curtain call and nearly forgot to bow.

After the show, she found him by the audience check-in table.

"You were amazing," she said, and her smile was so bright it hurt to look at.

"I didn't really have any lines."

"I know. But I watched you the whole time. You were so... present."

Present. Jason turned the word over in his mind. At home, he was invisible. At school, he was forgettable. But on stage, even without words, he was present.

They started dating in January. She wore his jacket even though it was too big. She held his hand in the hallways. She took him to parties and made sure everyone knew he was hers.

Jason wanted to make it deeper, to find something beneath the surface. He'd saved up enough money from his 7-Eleven shifts to rent a Skren VidLink booth at the mall—two dollars a minute, but it felt important. The booth was larger than a phone booth, with a built-in camera and a screen. You recorded your message onto a compact cassette-style cartridge, mailed it, and three to five days later the recipient could play it on their home VidLink console.

Jason recorded a message to Megan about a play he'd been reading, about his college applications, about wanting to understand her better. He talked for six minutes, twelve dollars gone in a conversation with himself.

Her response arrived five days later. Jason loaded the cartridge into his family's VidLink player—a boxy console that connected to the TV—and watched. The compression artifacts were immediate, the audio sync slightly off. Megan smiled at the camera, talked about a new necklace she'd bought, about drama with her friends. "Turn to Gold" played quietly in the background. She looked beautiful. She sounded engaged. The message was eight minutes of nothing.

Out of curiosity, Jason ran the cartridge through the MiyoVox's analysis input.

ENGAGEMENT METRIC: 8.7/10.0 GESTURE VARIETY: OPTIMAL RANGE VOCAL MODULATION: SUPERIOR QUALITY

"I am pleased to inform that subject demonstrates strong audience retention factor. Performance quality is superior."

Jason sat on his bed, staring at the scores. The machine thought Megan was compelling. It thought she was performing at a superior level. And Jason felt absolutely nothing watching her.

He tried twice more with VidLink—once asking her about her dreams, once about what scared her. Both responses came back glitchy and superficial, pixels fragmenting into green blocks, her voice talking about surface things while the machine praised her engagement metrics.

By March, he had run out of things to talk about with Megan. They still held hands, but it felt like obligation. She was nice. She was pretty. Her mouth tasted sweet and her softness felt good against him. She was everything he'd thought he wanted. And it wasn't enough.

Lenora moved to San Francisco in February, for a job serving coffee at Skren headquarters. Jason tried to maintain connection through VidLink, recording messages about drama, about his plans for college, about missing having someone who understood. He sent three cartridges. Two came back corrupted, unplayable, just static and green distortion. The third never got a response.

The technology that promised connection delivered hissing static. Jason still had MiyoVox footage of conversations with Lenora from months earlier—back before he'd been performing for metrics, when things had just been natural. Watching those recordings felt like unearthing an old documentary about the person he used to be.

The acceptance letter from Marlboro College in Vermont arrived on a Tuesday. Jason read it three times in his car before going inside.

At dinner—a rare event where all three Hartleys occupied the same room—he told them. His parents had removed their headsets for the meal, but they both kept glancing toward their bedrooms like prisoners calculating escape routes.

"Vermont?" his mother said, cigarette smoke curling from her nostrils. "That's across the whole damn country."

"It's a good school. They have a good program."

"What program?" his father asked, and Jason realized he couldn't remember the last time his father had asked him a direct question.

"Theater. Writing. Liberal arts."

His mother stubbed out her cigarette. "There are schools here. Perfectly good schools."

"I want to go."

They stared at each other across the table, and Jason saw something flicker in her eyes—not quite hurt, but close. His father just nodded slowly and went back to his spaghetti.

"You'll need money," his mother said finally.

"I have some saved. I got a scholarship. I can take out loans. I'll work. I'll figure it out."

She lit another cigarette. "I guess you'll have to."

After dinner, after his parents had retreated to their immersion zones, Jason hid the MiyoVox in his backpack and recorded the empty table, the three abandoned plates, the ashtray still smoking. The machine tried to analyze it:

SUBJECTS: ABSENT EMOTIONAL CONTENT ANALYSIS: INCONCLUSIVE

ENVIRONMENTAL DYNAMIC PARAMETER: UNDEFINED

Jason broke up with Megan a week later. She cried, which made him feel terrible and cruel in equal measure. For the first time since he'd bought the MiyoVox, he deliberately chose not to record something. The breakup happened without documentation, without metrics, without proof. Just two people in a parking lot, one of them leaving.

He drove home with Nine Inch Nails' "Head Like a Hole" blasting from his speakers, Trent Reznor screaming about control and refusing to give it. Jason sang along, his voice raw and cracking, and felt something shift. He wasn't rejecting just Megan. He was rejecting everything that used to matter to him—the metrics, the optimization, the performance for external validation. The machine's approval, David's approval, his parents' approval. All of it.

I'd rather die than give you control.

Lenora stopped responding to Jason's answering machine messages and disappeared into her new life in San Francisco. Mr. Carlson announced he was leaving to teach in Portland. Everything was ending, which meant everything was beginning.

Late August, and the Oregon heat sat thick and heavy over everything. Jason loaded the last box into his Datsun—a rust-yellow 1978 B210 wagon that had 180,000 miles and a prayer. The backseat was crammed with clothes, books, a CD player he'd bought at Goodwill. Everything he owned fit in one car.

The night before, Jason had gone through every VHS-C cartridge, every recording. Hours of footage: performances, his parents, Megan, himself. Documentation of a person trying to optimize his existence for an algorithm's approval.

He'd set up the MiyoVox one final time, recording without planning what to say.

"I was here," he said to the camera. "I existed in this house. I performed for you, and you never watched. I'm done performing."

He left the cartridge on the kitchen table with a note: For Mom and Dad, if you ever want to watch.

The MiyoVox itself sat in the passenger seat of the Datsun now, but it was turned off. He wasn't sure why he was bringing it. Maybe just to remember. Maybe to prove to himself that he could carry it without using it.

His mother stood on the porch in her scrubs, about to leave for her shift. She'd been crying earlier—Jason had heard her in her room—but her face was dry now, composed.

"Drive safe," she said. "Call when you get there."

"I will."

"It's a long way."

"I know."

She nodded, lit a cigarette, and went inside without hugging him. Jason told himself it was fine. This was how they did things.

His father appeared in the doorway like a ghost.

"You got enough money?"

"Yeah, Dad. I'm good."

His father reached into his pocket and pulled out a crumpled envelope from the bank. "Take it anyway."

Inside was two hundred dollars in tens and twenties. Jason felt something catch in his throat.

"Thanks."

His father nodded and retreated back into the house, back into his room, back into his silence.

Jason sat in his car for a moment, engine running, looking at the house where he'd grown up. The peeling paint, the overgrown lawn, the closed curtains. It looked like a place where people went to hide from their lives.

He put the car in gear and pulled away from the curb.

The highway stretched east, and Jason turned up the radio—Pixies on the college station, Black Francis singing about losing his mind. Jason sang along, his voice cracking on the high notes, not caring who heard.

He thought about David screaming at him to feel instead of think. He thought about Megan's perfect hair and empty conversations. He thought about his mother's cigarette smoke and his father's closed door. He thought about the difference between becoming present and being watchable. He thought about the MiyoVox's fuzzy, crackling metrics trying to measure things that couldn't be measured.

Vermont was three thousand miles away. He'd never been there. Didn't know anyone there. Had no idea what he'd find.

Somewhere in Idaho, the Datsun's engine made a concerning noise. Jason kept driving. He reached over and pushed the MiyoVox onto the floor, where it rolled under the passenger seat and disappeared from view.

The sun set behind him, painting the rearview mirror gold and crimson, and he didn't look back. Not once. There was nothing behind him worth seeing, and everything ahead worth finding out.

The road hummed beneath him, and for the first time in eighteen years, Jason felt like he was doing something real instead of just performing.

He turned up the radio and drove into the dark.